Never Disappear: Rowland S. Howard

Epitome of a talented early bloomer, Australian art school prodigy Rowland S. Howard came up at 16 with his first great work. Unexpectedly to friends and mentors, it would be in the form of a song called “Shivers”, a deceptively clever and touching tune that would create intemperate devotion in his homeland and continue to be covered worldwide nearly 40 years after its inception.

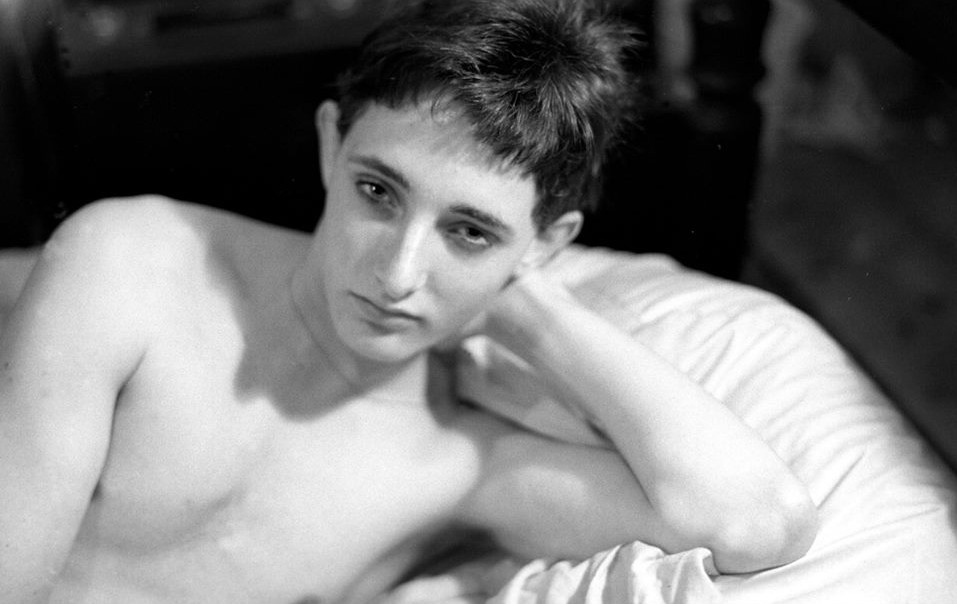

At such a sweet age, and in 1976, Howard anachronistically presented himself as a satisfying Isidore Ducasse figure: an intransigent youth, closed off perhaps but without borders when it came to imagination; a surprisingly tall, sliver of a child determined to channel his heroes in his art and down in the street.

As part of the compelling talking heads shedding light on the man and the artist in the 2011 documentary Autoluminescent, longtime colleague Mick Harvey recalls being dubious at first, deeming the boy “just a well-read dandy,” inadvertently disclosing the extent avant-garde Dada literary heroes were feeding the effete Romantic consumption-suffering image Howard was offering his then-tiny Melbourne world. Brother-in-arms Nick Cave adds in the same film that teenage Howard was already “fully-formed” in ways that inspired envy and annoyance in droves amongst his adolescent peers. Eventually and away from home, adult Howard would come to intimate danger and stridency in his musical output, sadly not an endearing combination for radio programmers and the public at large who missed how these severe qualities were enhanced with sensitivity, quietly dazzling wit, overall framed by the amused Pierrot features Howard would embrace and be blessed with until his death at the tail end of 2009. I learned of his passing on New Year’s Eve that same year, and in the world I occupy to this day, as for many others, Rowland S. Howard proves to stubbornly remain the great love-of-my-life I never met.

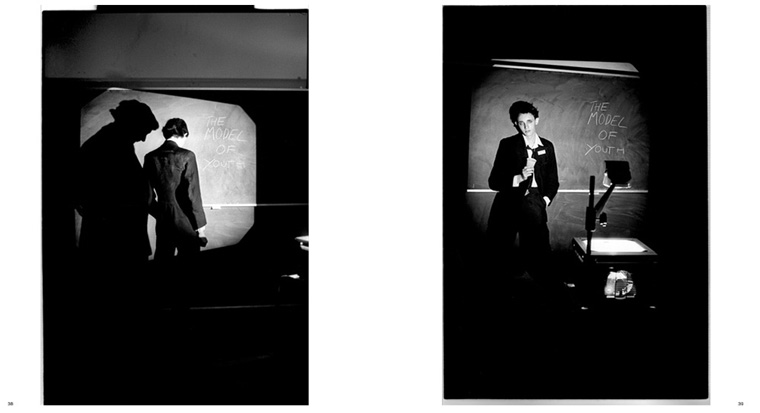

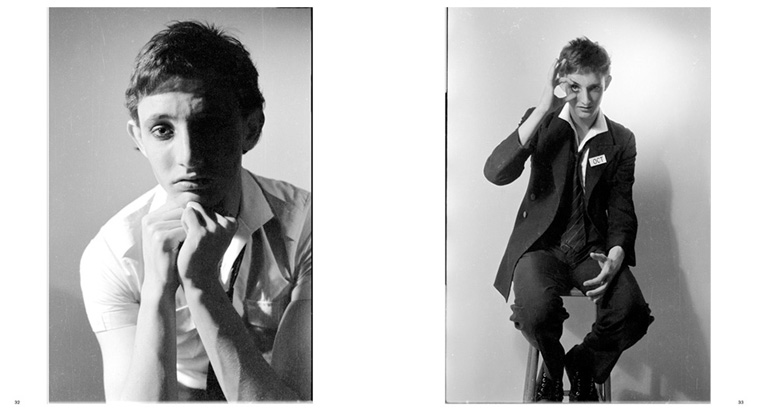

While Autoluminescent is a celebration of a complex life cut short and is additionally haunted by rare footage of Howard’s style and flourish over the years — even his postmortem words appear by way of excerpts from an unpublished novel — a recently published work reveals more of the mysterious making of a cult star’s image, by offering the classical Beautiful Boy aesthetics of the underaged Howard for all to see and marvel at. Artist Peter Milne’s limited-edition monograph A Day In The Life Of Rowland S. Howard will hardly remedy to any unrequited love for the boy. As a study in images of adolescence, this light-handed book of photographs taken by the author of his young chum in 1977 features some stunningly composed visual proofs of the elegance of youth, chaste homoerotic undertones sparkled here and there adding to the overall feel of innocence and the sense of an old, more deserted Melbourne frozen in time. To say that Rowland S. Howard was an ideal photographic subject is akin to stating the sky is blue, but it is the amateur essence of his poses that truly make the heart melt. As Milne himself mischievously declares in the book’s introduction: “We began a busy period of experimental photo sessions during which I was learning how to use cameras while Rowland was learning how to pose for them.” As rock & roll visual history came to attest, Howard would quickly become a professional at projecting on film, from analogue to digital, the visual essence of his musical output: photogenic airs at once prickly and sweet, never bitter, and certainly not ordinary.

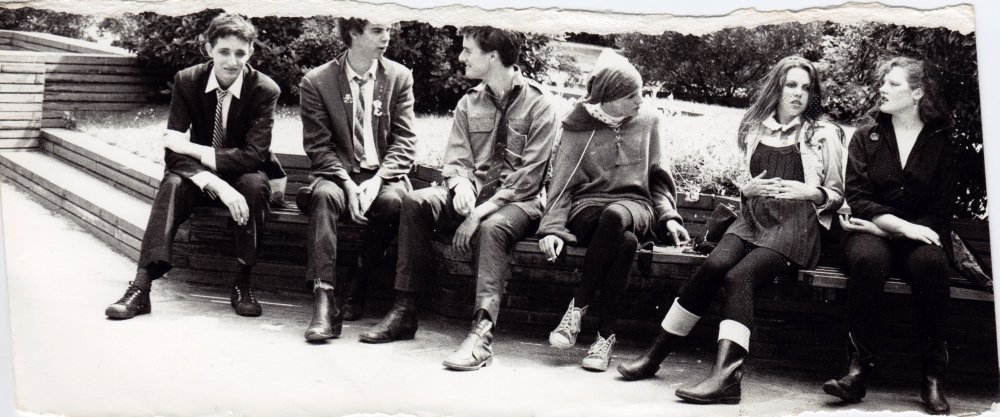

Howard may have been the undisputed lead of his own photogenic life but he was supported by compelling guest stars all through it: friends, loved ones, collaborators — they would often blend into one one and the same — would go on to develop into magistral characters. In 1977, this sweet gang of future luminaries — including Anita Lane, Ollie Olsen and Mick Harvey — were still in their undeveloped, and touchingly so, infancy. While Howard’s charismatic and angular homme fatal features already traverse the third wall of the page, soon-to-be-iconic companion Nick Cave, for instance, looks goofy and awkward in comparison, qualities he would later spectacularly twist and turn and use to his advantage, but not here, not yet. Our current age of déjà-vu-everything tends to erase the memories of how striking the punk and New Wave fashion looked to the eyes of 1977 contemporaries. A photograph of a slouched Howard, flanked by Milne attentively reading a recent issue of Playboy, reminds us of the esthetic clash between these young ones and the outside world. The cover of the magazine features an arched, barely nude David Hamiltonesque model bathed in soft sepia light, sporting what looks like quaint 1930s gauze apparel and floppy hat, while the contrasting photograph (taken by co-conspirator Bronwyn Adams) of Milne and Howard sitting on a sofa is all harsh minimalist black and white edges, a defiant stare on Howard’s frosted face.

Big Biba fans these kids were not.

(Photographs: Peter Milne)