Lana’s Adolescent Sadness

This might be #throwbackthursday but Lana Del Rey moves resolutely forward: today she announced the track listing of her upcoming Honeymoon LP and it has hardly been a year since her last album emerged, a record that had left me a little cool despite falling hard for “West Coast”, sound and vision.

To be fair, my halfheartedness had little to do with the quality of the end product; more a question of last year’s Ultraviolence’s themes and arrangements’ diminished flavor on my musical taste buds. The songwriting and overall execution of her 2014 project clearly proved effective for most: reviews were overall positive, her fans kept the flame alive and it sold well. But what had initially drawn me into Del Rey’s world when she’d emerged renamed and renewed with her faux-debut Born To Die was her portrayal of adrift, wannabe good but mostly stumble down the wrong side of everything, characters. Whether the artist sang about her fictional self or her fellow gal pals, she had placed the lyrical focus on unfulfilled coming-of-age women, telling the story of barely adult females facing the treacherous and confusing demands of their emotions and desires. This had resulted, indirectly perhaps, in a sharp, accurate and disturbing picture of society’s veering-on-unsound obsession with very young women.

When Del Rey entered our popular consciousness hardly four years ago through her much maligned performance on Saturday Night Live, she was met with such dissent it felt for a while this very denunciation was the supposedly well-orchestrated marketing ploy decried by countless critics. Attacks seemed to generally narrow down to these elements: her authenticity or legitimacy as a “real” artist, and her negative impact as a role model. The first point was debated at large and frankly, I find it a non-issue then or now; I was more puzzled by the idea that we continue expecting, occasionally demanding, that some artists’ personae have a positive moral influence on youth or on our culture, which strikes me as particularly suspect since this requirement rarely seems to apply to male controversial figures, especially white ones. It’s misleading to give such power of influence over millions to a sole celebrity regardless of the personal and sociocultural circumstances of the individuals affected, as if a person’s values and personality were irrelevant. Freedom to create a multifaceted, sometimes unpopular image is key to the creative process in order to reflect the complicated and less savory realities of human experience. Pressure to conform to a prevalent rigid model often proves an excellent tool in the hands of proponents of conformity, always just a stone’s throw away from censorship.

No one could accuse Del Rey of treading lightly in the commercial world. After the initial criticism she’d faced regarding her lyrical themes and self-described “Lolita lost in the hood” image, to name an album Ultraviolence, which under any circumstance would prove controversial, and release a title track that bluntly addressed the subject of domestic violence — accompanied by one more signature vintage-looking video, this time depicting a seemingly contented soon-to-be bride — could be interpreted in many unflattering ways if one decides to ignore the subtle levels of meaning herein contained. There has always been a strong correlation between elation and self-destruction in Del Rey’s lyrics, as with her post-modern reimagining of a derivative easy-on-the-eyes seemingly passive persona. Ultraviolence helped mask the degrees of significance previously displayed in Del Rey’s lyrics, as the album’s main motif centered rather on the grand temptations of romance and fortune than on the drama of, and eventual adjustment to, innocence lost, which filtered Born To Die.

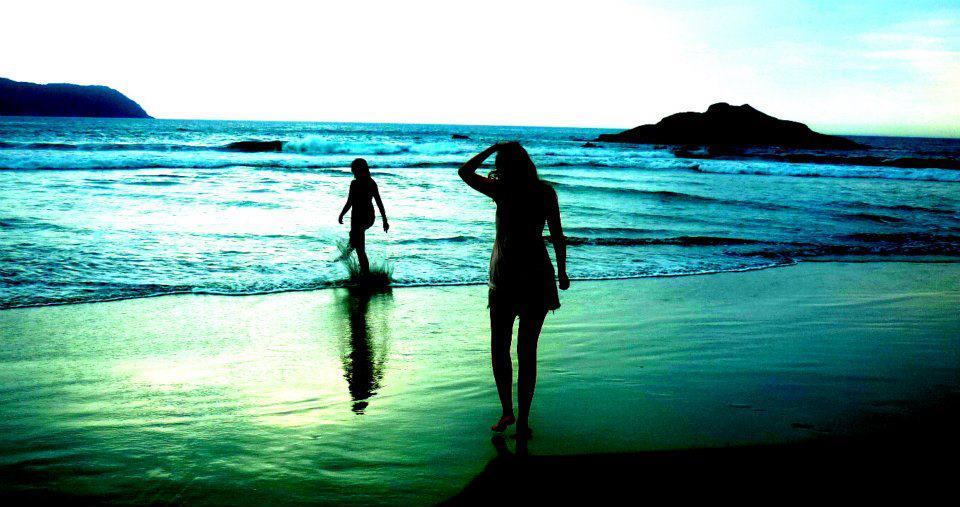

The last single of Del Rey’s breakthrough was to be “Summertime Sadness,” a song that would not easily disappear thanks to Cedric Gervais’ popular remix, heard every day arising from passing cars and patios on those lazy warm evenings two summers ago. Lately I have been embracing the remaining languorous August heat by reacquainting myself with Born To Die; “Summertime Sadness” was resuscitated by a neighbor with an excellent sound equipment a week ago, and I decided to watch the video for the first time. The short film features a juvenile-looking Del Rey and a fellow young woman playing the parts of lovers/girlfriends, both on the brink of annihilation in Christ-like poses, shrouded in hazy light, shot slightly out of focus, in pure and plain Del Rey aesthetic. This video might be the most outright depiction to date of Del Rey’s thematic of female adolescent friendship, a formative period when best friends are sisters, partners, confidantes, conspirators; a relationship felt and lived with genuine intensity and the passion of love. To confirm my theory, I sent the video with no further explanation to my oldest ally; she and I have sustained a friendship born at a time when “bff” did not even exist decades ago. She is a cultured, classy and busy woman who now has little time to delve in the Anglo-Saxon pop music world of our youth. Her immediate text reply? “Splendid and intense. Thanks for this trip down my faraway past and memories, hon.” The critics may not know, but the grown up little girls understand.

Enjoy the last days of summer.