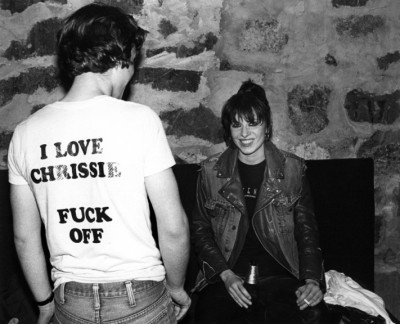

It is a peculiar thing for a woman to find herself forced to walk the tightrope between preconceived definitions of masculinity and femininity but it has been frequent in popular culture and especially in rock and roll, a noticeably masculine world where the lack of varied female role models endure. Thirty-five years ago, at a time when words like cisgender, normative and most discussion of sexual politics were uncommon if not completely absent from everyday conversation, Chrissie Hynde was the cool rock god-and-goddess on the radio, the one to worship in the mainstream pop world.

Back in the early 1980s, Hynde’s allure read as masculine, her clothes and stance remarkably androgynous for a highly visible female star occupying the music charts with her melodic and catchy songs, and whose tender, vaporous voice translated as unmistakably “feminine.” Hynde also bypassed other seemingly unavoidable and superficial rock stereotypes for a female musician part of a group. As a woman-in-rock, Hynde was not part of a “girl band,” a double-edged descriptor outfits solely comprised of female members still have to contend with today; she did not front a band based around a romantic partnership with a male beau, creatively at best credited as the co-writer of the band’s songs; and she was not considered the “girl in a band”, the cliched image of the quiet member playing the part, frequently despite themselves, of the sexy-cool-hip chick used as unthreatening novelty factor while taking a backseat to the group’s main men. Of course, these female rock and roll standards hide the full scope of the female artists they describe but they were, and remain, extremely hard to avoid. Hynde’s unique trait was that she was not part of a band: it was a fait accompli that she was the band, the leader of her pack and therefore incredibly alluring to boys and girls like myself who were uncomfortable with traditional role models.

The Pretenders were Hynde’s undisputed brainchild and creative vehicle. This is a fact that she reminds us of — as it bears reminding — and which is at the core of her memoir Reckless, a brash, blunt and honest account of how a young female music fan vigorously and painstakingly builds her own destiny, along the way taking what life throws at her expectations in stride. Hynde may have wanted her autobiography to be a cautionary tale to young people, especially to young girls, but despite one of its themes being substance abuse leading to instances of poor judgement, the book reads as a rock and roll female fan’s journey, one aspect of her story that deeply resonated with this once little music fangirl. Reckless fills in the blanks Hynde was often too impatient to bother explaining in interviews over the decades, including the traumatic event that has recently been used in the media as controversial soundbite — I would even say as sound bait — but that she had been open about before (that sexual assault is after all the subject of her rocking tune “Tattooed Love Boys”). Reckless certainly contains its fair share of perils of the rock lifestyle stories and true to the author’s personality, some pretty risky phrases, but reducing over 300 pages of a person’s real-life tale to the equivalent of one controversial paragraph is akin to judging a human being based on their Facebook profile. Instead of verbal attacks and more victim shaming, Hynde’s comments should lead to an open and needed discussion of the very real and very different “perils of rock and roll” men and women face.

The portrait Reckless paints of Chrissie Hynde is that of a woman who wanted to live like a man, an expression we finally understand in 2015 as what it has consistently meant in the mind of women: possessing the same rights, privileges and all-access passes accorded to men in our society. Growing up, Hynde wanted to be able to enjoy the rock music she loved accompanied by her girlfriends without getting groped at concerts; have the freedom to feed her curiosity and explore her physical world by walking alone on the streets of different neighborhoods at any hour of the day; do drugs with anyone she felt like without the fear of negative sexual consequences. Hynde wanted to be independent and free to create her own complex female role model in a world where given choices have generally been virgin or whore, bold dualistic terms Hynde herself would not discredit. Growing up a fan of rock and roll and dreaming of a more countercultural or untraditional life means having predominantly, if not solely, male models to admire and emulate outside of the reductiveness of the good girl/bad girl types — I’d argue this was especially true up to twenty years ago. The welcome memoirs of female musicians that have been coming out lately are a recent phenomenon: Marianne Faithfull’s autobiography may have been the second well-known rock female musician’s memoir I’d ever read (after Michelle Phillips’), 99% female rock and roll book authors I had come across having been self-described groupies, wives and girlfriends of male stars, or behind-the-scenesters. What is generally considered the obligatory “cool” novels and poetry to read, the classic records to own, the now iconic movie masterpieces to watch, these are usually made by and populated with similarly “cool” dudes. Where are the ladies in these countercultural books and movies? Certainly not wanting to walk home unaccompanied by a male escort at four in the morning or attending concerts on their own because they’re not children; and certainly not doing blow in the back room with the gang and partaking in shenanigans but wanting to keep their clothes on all evening. The thrill of rock and roll music for a male or female fan is identical, and the sense of adventure of the independently spirited individual looking to live a different lifestyle is felt the same way as well, but the reality once out there in the rock community is that the life of a rock and roller is still lived differently for each gender. It would be naive to think unconventional actions in any society bear no consequences but they stubbornly remain distinct for men and women, with a predominantly sexually dangerous component for women, specifically young ones. This greatest of injustice of living as female will probably persist for a long time and as long as it does, it will need to be addressed.

Reading Reckless brings back memories of my own initiation to the exhilaration, joy and perils of rock and roll, and of the many transcendent moments, risky situations and definitely bad decisions made too. Working on another writing project a few months ago, I was attempting to explain why a particular sinister song was so appealing to the listener. The song features a car stopping by the curb, a stranger driving it and a pedestrian looking in. My question was, “Why did the individual get in the stranger’s car?” as I remembered that old adage: don’t talk to strangers, which never made much sense to me. If we never talk to strangers, how do we communicate in the world? But more to the point: what makes us want to approach and interact with people in the first place, a desire I consider deeply basic and healthy. I think we get in the stranger’s car because as people we simply hope, and as a species we never lose our sense of hope. We hope people are essentially good, we hope we will have fun that night, we hope we will meet kindred spirits to build a community we can finally belong to. In that sense, Reckless is about Chrissie Hynde searching the only way she knew how for her people and finding them, with the addition of mayhem and sorrows along the way but that too is a risk of living in any world, mainstream or subcultural. Possessing the talent and craftsmanship of the rock and roll icon she would become, she used her art to transform those woes and convert them into superb music. In that respect, Reckless becomes a very human tale of hope in that tough world of sex, drugs and rock and roll.