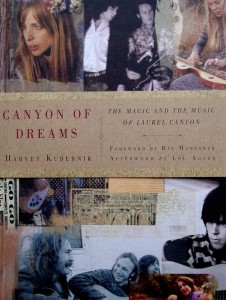

Canyon of Dreams: The Magic and the Music of Laurel Canyon by Harvey Kubernik (Sterling Publishing)

Review & Interview with author by Sophie-Françoise Faithfull

Legendary record producer and music man galore Lou Adler called it, “A slice of nature hidden behind a neon sign”, the paradise on earth of the modern age, a stone’s throw away from one of the largest megalopolis of our time. Mythical Laurel Canyon, the lungs of downtown Los Angeles and Hollywood, seems indeed to be a magical, surreal place, where for decades now folks from all over the world have been mysteriously drawn to. For the first time a book manages to capture the entire scope of the famous canyon’s musical history and tradition, which did not start with Joni Mitchell’s recorded ode from 1970 but go back to the creation of this fascinating city itself. Formidable music historian and native Angeleno author Harvey Kubernik serves as our guide into seemingly familiar yet uncharted territory, with his gorgeous coffee table book Canyon of Dreams. Filled with first-hand reminiscences from key players and behind-the-scenes observers, all sharing tales of a place anyone in love with popular music or the 1960’s culture is aware of and fascinated with, this major work, heavily illustrated with the stunning photographs of Henry Diltz, is needed more than ever to bring some magic back into our lives, and be a source of beauty in dire times. Laurel Canyon will never completely lose its mystery but we will never stop yearning to know more about its alluring ways.

Legendary record producer and music man galore Lou Adler called it, “A slice of nature hidden behind a neon sign”, the paradise on earth of the modern age, a stone’s throw away from one of the largest megalopolis of our time. Mythical Laurel Canyon, the lungs of downtown Los Angeles and Hollywood, seems indeed to be a magical, surreal place, where for decades now folks from all over the world have been mysteriously drawn to. For the first time a book manages to capture the entire scope of the famous canyon’s musical history and tradition, which did not start with Joni Mitchell’s recorded ode from 1970 but go back to the creation of this fascinating city itself. Formidable music historian and native Angeleno author Harvey Kubernik serves as our guide into seemingly familiar yet uncharted territory, with his gorgeous coffee table book Canyon of Dreams. Filled with first-hand reminiscences from key players and behind-the-scenes observers, all sharing tales of a place anyone in love with popular music or the 1960’s culture is aware of and fascinated with, this major work, heavily illustrated with the stunning photographs of Henry Diltz, is needed more than ever to bring some magic back into our lives, and be a source of beauty in dire times. Laurel Canyon will never completely lose its mystery but we will never stop yearning to know more about its alluring ways.

Laurel Canyon, for anyone not born and raised there, perhaps for anyone at all, feels like a throw back to a time of pure energy and creativity, partially due to its musical (and cinematographic sister) history, and also its breathtaking delivery. Life here is presented to you through a constant ambience of warmth, sun, blooming trees and yet, modernity. As you arrive from Sunset Boulevard in the city, that famous Strip, you must drive up a winding hillside busy street, the Laurel Canyon Boulevard, that will bring you to shangri-la itself, away from the commotion and urban insanity of the metropolis. The place brims over with the electricity of the city but set in bucolic green woods. Fragrant lavender and eucalyptus plants share the space with palm and lemon trees on the hills; at night, mountain lions stare fearlessly at the residents while coyotes provide the soundtrack; tortuous roads springing up here and there lead ever higher towards the sky, offering million-dollar views of the city of angels. It is telling that the Canyon is a former turn of the century summer retreat from the city heat; the tavern roadhouse shack is still there on Lookout Mountain Avenue. Who wouldn’t want to come here? Perhaps because it was never a distinct single-purposed town but a community of free-spirited individuals and dreamers passing through and staying awhile, the architecture is all over the place: whimsical cottages and mid-century bungalows lie happily next to Spanish colonial mansions and Rocky Raccoon cabins, not to mention the gated modernist manors that are all glass windows perched at the top of the most expensive peaks.

The beautiful people seem to always choose to live on hills and mountains, above the common ground and common folks, above the mundane and the vulgar. Such a paradise as is Laurel Canyon and its neighboring sisters Benedict, Coldwater and Nichols Canyons must accordingly attract some darkness to balance the immense, comforting light: Mother Nature sends destructive fires and earthquakes while man takes care of homicide. These are part of the Canyon’s complex history, and are perhaps more shocking in such a nirvana-esque context. This evil may appear to be a reflection of the city of angels itself, such an interesting and strangely balanced mixture of New Age, soul-searching spirituality in a pure hedonistic setting, countered by the down-and-dirty money-making (show)business and cut-throat values. The city is at once fascinating, appalling, invigorating and frightening, all together implying a big dysfunctional family of emotions. Laurel Canyon, with its largely residential ways – it has only one legendary store after all – feels built for the people, not the consumers, and as a result is incredibly refreshing and peaceful.

As it stands, Laurel Canyon as a “town” is a different kind of neighborhood. There are no shopping malls, a mainstay of the new American way of life; no clothing store, with the exception of the occasional semi-private room full of second-hand treasures; no high rise condo or grotesque architectural eyesore, and especially important: no nightclubs or restaurants. The whole feel is “homey”, not only because of its highly rural quality, but because life here happens in-house, so to speak. You drink, do drugs, play music, dance, jam, discuss, meet up, make love, surf the net, all in homes, around homes, in the backyard of your home. So many secluded corners could be breeding grounds for trysts, bacchanalia, seances, privacy; the stuff life and dreams are made of. For anyone ultra-urban and used to living downtown or in any city, life in the Canyon resonates as breezier, intimate and free-flowing, as opposed to free-falling, harsh and awkward. All through its history, men have come here seeking to reinvent themselves, to get away from something old, to produce something new. Women, well, they probably to some extent did the same, but the ladies of the Canyon hold a special place in musical history, as muses and often catalysts to the music itself. Weren’t they a big part of its appeal, after all? In the decade that put the Canyon on the map and changed everything, at the birth of the Second Wave of feminism and self-discovery for all genders, when “sexual politics” meant who you were sleeping with that week and not yet a discussion of sexual identity, the ladies, those unknown goddesses, were the anchor of many male scenesters and creators, a “home” made of the eternal feminine, a way to get back at The Man, a mystery worth exploring. Nowadays, those new goddesses are more than ever acting, shaping and reshaping the scene, in the spotlight and behind the screen, true equals at last in the making of the artistic masterpieces of tomorrow. There is after all one building that stands out in the Canyon, and it is not a gigantic mansion or a cooler-than-thou hang-out: it is a simple elementary school at the foot of Wonderland Avenue, where are thriving and growing, one can hope, the future legends of the Canyon.

The delicious book Canyon of Dreams could serve as the bible of the Canyon: rich in anecdotes and first-account stories, incredibly vivid and grabbing yet filled with addresses and dates for the amateur historian detective in all of us, backed by truly gorgeous photographs and candid, telling moments, it helps perpetuate the legend surrounding the place. A large portion of the narrative is about the decade that interests us most, of course, but being aware of the entire 20th century musical history of the area helps put things in perspective, since the main question when it comes to Southern California has always been: why are so many attracted to the West Coast? The book may not offer any definite answer but it certainly helps in understanding the appeal, and if you are lucky enough to have visited the Canyon, you may use it as a beautiful handbook to justify staying there.. just for a while. Now give yourself the right to surrender your mind and body to Laurel Canyon and its enchanting ways.. and enjoy your precious life.

Interview with Harvey Kubernik, author of Canyon of Dreams: The Magic and the Music of Laurel Canyon (Sterling Publishing – 2009)

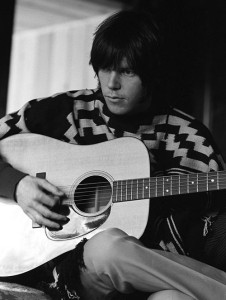

Harvey Kubernik has been working in Los Angeles for almost five decades as a music journalist and author of numerous books including This is Rebel Music: The Harvey Kubernik Innerviews and Hollywood Shack Job: Rock Music in Films and On Your Screen. His resume could also add record producer, A&R man, cultural researcher and archivist, music advisor and popular music historian to that list. His knowledge of the musical, social and cinematographic history of Southern California is comprehensive, not to say mind-blowing. Here he candidly shares his thoughts with Misty Lane regarding his most recent book on the legendary Laurel Canyon scene.

Misty Lane: Considering your extensive knowledge of Los Angeles’ cultural and musical history, what made you decide to focus your attention on Laurel Canyon specifically, and what prompted you to release a book about it at this time?

Misty Lane: Considering your extensive knowledge of Los Angeles’ cultural and musical history, what made you decide to focus your attention on Laurel Canyon specifically, and what prompted you to release a book about it at this time?

Harvey Kubernik: I’ve always been writing and researching Los Angeles, and especially the

Hollywood musical legacy. Two years ago I was asked to write the liner notes for the expanded CD reissue of Carole King’s Tapestry album, a definitive Laurel Canyon audio artifact.

Right on the heels of that Tapestry liner note gig, coupled with the concurrent plethora of cover stories I’ve written the last decade for Goldmine Magazine, MOJO, as well as my own earlier books and more recent literary endeavors, a book packager contacted me when he received a call from a publisher who wanted a Laurel Canyon book. When they sent a contract, that prompted writing about the area right now.

ML: Laurel Canyon is a special place; I’ve felt it during my visits and stays. It is not only the location and landscape that make Laurel Canyon such a ground zero for many musical endeavors in different genres. There is something else that’s undefinable. In your personal opinion, what makes this canyon so “magical”?

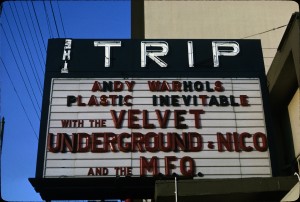

HK: One of the reason the Canyon was so magical and still offers some magical moments was that the region from the 1940s to the early 1960s always had jazzbos, beatnicks, artists, poets, writers, painters, actors, HUAC (House Un-American Activities Committee) victims, hot girls and cool guys. Laurel Canyon was 5 minutes from Sunset Boulevard and Hollywood. Because it was partially hidden away from the streets and congested neighborhoods, you could get away with a lot of things in Laurel Canyon. Legal and illegal.

So, all the ’60s and ’70s musicians and bands and subsequent albums that you and your readers worship partially emerged because many people and musicians, including open-minded record label owners, who resided in Laurel Canyon, set the scene for the new transplants, freaks, and aggressive driven artists to relocate and get as close as they could to recording studios and the world of Hollywood.

ML: Your book tells the tale of roughly seventy years of Laurel Canyon history, showing the tight link between the music and the film industry over several decades. What attracts so many musicians to actors, and vice versa?

HK: It’s a very short drive to Sunset Blvd. from Laurel Canyon where from 1940 to 1990 many record labels and music production companies and music publishers were based. The musicians were also attracted to recording studios like Sunset Sound, United Western and Columbia on Sunset Blvd. The actors were near television and movie studios in Hollywood, and could also drive over Laurel Canyon into the San Fernando Valley to studios like Universal and Warner Bros. (By taking Laurel Canyon Boulevard that crosses the canyon from Hollywood to the San Fernando Valley)

ML: Speaking of the link between cinema and music, I recently watched Lisa Cholodenko’s excellent Laurel Canyon (released in 2002), featuring Frances McDormand as a prototypical Laurel Canyon bohemian baby boomer, and her tense relationship with her yuppie son played by Christian Bale. The film reveals a brutal shift in values from the 1960s/1970s to the millennium, and the palpable tension between the two main characters, which reflects the changes in the Laurel Canyon mentality in the last few decades. It is telling that the son’s wife, a Canyon “outsider” has a more nuanced view of the life and values of the mother, and of Laurel Canyon itself.

Any thoughts about this? And how would you say this shift in values and culture in Laurel Canyon since the 1960s is represented in your book?

HK: No real thoughts on this specific film. Someone just gave me a copy of it on video. I made it a point not to see any Laurel Canyon-related products these last few years. Although I was the photo editor over a decade ago on Barney Hoskyns’ Waiting For The Sun and helped him on that book about the history of Los Angeles music. Most of the folks who moved to Laurel Canyon didn’t bring a whole lot of values in the first place. They came to California armed exclusively with goals to make it in show business. Ninety per cent of these visitors I think you are addressing came to town to fuck and flee.

The book might possibly show a shift in values and culture by the simple fact that just about every musician or singer-songwriter, or vocalist, who came out West and lived in Laurel Canyon from 1966 to 1973 moved to other canyons or to the beach or out of State as soon as they had a hit record or successful album on the charts. These people were always careerists, which is fine.

Their music did help shape the mindset and the media preoccupation with what they still think the sound of Laurel Canyon is and was.

I made it a point in the book to put a focus on the longtime residents and native Angelenos and most of the home owners or renters who stayed for at least 5 to 15 years. These people always had values and informed the culture. They shaped the specific audio world in that zip code. Their music always reflected the neighborhood. Some of it was recorded inside their homes in the neighborhood. They have children who went to Wonderland Avenue Elementary School and then later attended high schools in the area like Hollywood High or Fairfax High School. Some went to nearby private schools.

So the shift in values and culture you might be talking about can possibly be linked to the siege mentality or show biz wannabes who came to town for the sole purpose of scoring a record deal or get in the movies. There were always independent people around who had the values and were the culture-makers, or helped define the regional sounds. They usually stayed around longer. You hear and feel them breathing in my book. Canyon of Dreams also underscores the movement in the canyon: earthquakes and economics are linked together, but the concentration is on the music.

ML: The narrative of the book is quite lively, thanks to the use of quotes from interviews with Laurel Canyon players who are still alive today and can reflect on the past and compare with the present. Was focusing on musicians and music producers who are still around today intentional, and how did you get so many talented and legendary people to participate in your book? And how do you think this affects the importance, in retrospect, of some major musicians active in Laurel Canyon who have since passed away — Gene Clark comes to mind?

HK: The narrative is quite lively and potent because I encouraged long form display and not short sound bites. I served the book and the music and kept my ego out of the way for the most part when it came to questions and answers from the participants and contributors. I let them speak and define the world. However my vision is totally obvious on the page as well.

When I took this assignment I insisted that besides musicians, music producers and arrangers, fans, hitchhikers and record geeks would be incorporated into the mix and visuals. Not just white rock bands either. It was also going to be oral history-driven. The keyboardist often has a better memory than the lead singer or the tragic figures the media sometimes focuses on. I got so many people to participate and collaborate with me because I am a terrific music historian, and a passionate and original writer. I was first published in the Los Angeles Times in 1974. A handful of the musicians really wanted to talk to me because they felt some other books about Los Angeles and Hollywood or about Sunset Boulevard were poorly researched and written. For others, their publicists wanted to steer them into this book. I graduated from Fairfax High School, a mile and a half from the entrance to Laurel Canyon. Our Driver’s Education class was in Laurel Canyon.

I also hear and feel the music deeper than most others that tried to write about the area. I was there. I sold and distributed newspapers on Sunset Blvd.; I danced as a teenager on the music shows in Hollywood. Now my words dance. Those of us fortunate to have been born then and have a memory back to the mid and late ‘50s, it’s like seeing The Beatles in Hamburg or The Cavern Club. Los Angeles was still a town, and then the entire world wanted in and decided to move out West to Southern California (in the ‘60s). One of the reasons your readers and I dig The Doors, Love, Turtles and The Beach Boys is that these are bands that were made up largely of local kids and college students. The initial motivation and plans were initially more regional and organic in design.

As for the deceased artists and players, the music lives on if the person is not on the physical planet. I remind the reader of their work and legacy. Not only the cult musician, but the forgotten band member they failed to embrace. I know I brought some attention to some folks like Barney Kessel, Gene Clark, Canned Heat’s Al Wilson and Bob “Bear” Hite, Lee Wilder, Arthur Lee, a well balanced and new view of Jim Morrison, and an original and unique profile of Frank Zappa.

Along the way I placed visuals of venues, bands and settings that remind us of the places and people parade that existed before they investigated my book. The book’s narrative is reinforced by the inclusion of over 300 photos. They serve as collective memory scrapbook.

ML: The 1960s are heavily represented in the book, as it seems to be the peak of Laurel Canyon’s musical prominence, and the main reason for its legendary status today. What is the Laurel Canyon music scene like today? You mention a few current artists in your book; who are the up and coming musicians and creators you can identify as being the true sons and daughters of Laurel Canyon?

HK: The area still has a heartbeat. I made sure to devote a large last section on the music of Laurel Canyon from the last decade. Lots of bands, singers, musicians, music supervisors are in the area. The group Entrance is one of my favorites. I believe their new album is out on a label operated by Sonic Youth and distributed by Universal Records. I also like Jonathan Wilson, who just split the scene and is someone to watch. Zowie Scott, a singer-songwriter, too. The DJ/record producer Steve Aoki is in the area, same as Linkin Park. Bill Mumy also comes to mind, who has put out nine solo albums. Check him out. Tommy Morello of Rage Against The Machine lives in Laurel Canyon.

Regarding the current energy of the canyon, “different strokes for different folks” as Sly Stone suggested. Couple that with white flight, a move to the suburbs, new money and the fact that most new musicians concentrate on fashion and the videos in their head, and a mindset about the A&R person or record label they want to be on. Nurit Wilde and Henry Diltz in the book also acknowledge that Laurel Canyon was not the best place for young children to grow up because of the lack of parks or big areas for bike rides. So a lot of residents moved once they had children who were ready for school.

The Laurel Canyon world fans like you worship has lost some of its energy. Struggling artists can no longer afford to live in Laurel Canyon. Read Catherine James’ comments on rent increases in the book. Van Dyke Parks points out that the musicians decades ago could live in a band house or rent one for 200-300 a month. It’s five times that much these days. So, the socioeconomic structure does not allow for the music to be developed or nurtured because everyone is sweating rent, let alone paying for a practice space.

ML: It is telling that the presence of female artists in the book seems to be minimal, with the notable exception of pioneers like singer-songwriters Jackie DeShannon and Joni Mitchell. Are you noticing more women involved as creators and instigators today than in the past?

HK: I think you might be wrong about the minimal presence of female artists in the book. You cite Jackie DeShannon and Joni Mitchell yet you fail to acknowledge that in my book there’s inclusion, discussion or first person quotes by Cher, Michelle Phillips, photographer Nurit Wilde, Mama Cass Eliot, a whole entire chapter on Carole King and her monumental Tapestry album. The bass player in Entrance is a woman but I don’t mention she’s a female. I made sure to address the children’s market with a photo of the man and woman team of Rene Stahl and Jeremy Toback. There’s also multi-instrumentalist Lili Haydn, authors Pamela Des Barres and Catherine James. I displayed clothes designers like Ola Hudson, Guns and Roses’ Slash’s mother, in sidebar sections and running commentary. Wherever I could in photographs, the women were largely portrayed professionally with their musical instruments: Carole King at the piano, Lily Hadyn with violin, Zoe Scott and Priscilla Ahn with guitars.

As far as the other question about women being more involved in creation and instigation of regional music and audio pop culture in general, initially, decades ago women were basically companions, fans, “musician pals,” singers, reporters/writers, record store clerks, and then as musicians started writing their own songs, playing their own music, securing indie and major label record label deals, and in some cases, establishing their own record companies with time. The chicks that I meet at my book signings or who come up to me want to be in the movie and film business, not really the music industry. They might have started in bands or played around town for a while, but some have set their goals on Film School, or want to be screenwriters, directors, PA’s, interns at film festivals, or position music they like into a movie product as music supervisors. From what I gather, many others are concentrating on other roles and worlds like promotion, production, video and film work behind the camera, which are good collaborative mediums. Girls always support and advance the music. As Howlin’ Wolf sang, “The men don’t know but the little girls understand.”